Volunteer Drivers Toolkit

RESOURCES > TOOLKITS

Table of Contents

- Welcome

- RTAP Program Overview

- National RTAP

- State RTAP Programs: Status and Trends

- In-House And Outsourced Programs

- RTAP Program & Components

- Training

- Technical Assistance

- Marketing and Education

- Scholarship Programs

- Conferences and Roadeos

- Research and Data Collection

- Records Management

- Networking and Professional Development

- New RTAP Manager Succession Planning

- Sample Documents and Templates

Volunteer Driver Programs

Public transportation, which includes Tribal transit, urban, and rural transit systems, as well as human services transportation, encompasses a broad range of services designed to meet the mobility needs of population groups who have few if any options for travel. Older adults, people with disabilities, veterans, and people with lower incomes are often in particular need of greater mobility options. Depending on their abilities, their environment, and the transportation services available in their community, these individuals may also require a variety of mobility options. Volunteer driver programs and organizations that choose to sponsor volunteer driver programs help to fill critical mobility gaps for people who live outside public transit service areas, need to access jobs or services outside public transit service hours, or need more personal or specialized services to travel.

Organizations like Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), Community Action Agencies, independent living centers, faith-based organizations, urban, rural and Tribal transit systems are well suited to serve as sponsoring organizations to volunteer driver programs. Sponsoring organizations provide necessary structure, financial oversight, and liability coverage.

This section of the Toolkit introduces specific things an organization should do as a standard part of planning, implementing, and operating a volunteer driver program. It provides an overview of requirements, processes, and procedures known to be of value to volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations. Methods and practices used by a variety of volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations are included as examples throughout.

- Volunteer Driver Programs

- Volunteer Driver Programs and Sponsoring Organizations

- Mission Statements, Goals, and Objectives

- Rider Eligibility

- Limiting Financial Exposure Related to Risk

- Tips for Understanding Volunteer Insurance

- The Volunteer Protection Act of 1997

- State Laws for Nonprofits and Volunteer Liability

- What Type of Insurance is Needed?

- Liability Insurance

- Property Insurance

- Volunteer/Employee Dishonesty

- Medical Insurance

- Risk Management

- Post Sedation Transportation

- The Importance of Community Relations

- Community Outreach

- Marketing

- Branding

- Policies and Procedures

- Organizational Policies

- Emergency Management

- Personnel

- Funding

- Local, State, and Federal Funding

- Subcontracted Services

- Operating Across Borders

- County Borders

- Mobility Management

- Additional Reading on Other Types of Volunteer Driver Programs

- Section Resources

Volunteer Driver Programs and Sponsoring Organizations

While some volunteer driver programs are not supported by a sponsoring organization, most fit into a local or regional community service provider’s services. The sponsoring organization is the key element in the development and operation of many volunteer driver programs.

A volunteer driver program and a sponsoring organization:

- Should be of sufficient organizational strength and structure to manage a volunteer driver program. A volunteer driver program will require processes and policies that are specific to the establishment, administration, and operation of a volunteer driver pool. Organizations that operate volunteer driver programs should also have sufficient financial management systems to account for and report to funding agencies, and overall should practice sound financial management practices.

- Should set Mission, Goals, and Objectives for the volunteer driver program. Mission statements, goals, and objectives from a variety of volunteer driver programs are included in the section below and are included with each case study in Section 7 – Case Studies.

- May choose to limit the exposure of their volunteers, their governing board, and their staff. As an example, under Washington State law, RCW 24.06.035 Indemnification, it is possible for a Sponsoring Organization, private for-profit or non-profit, to amend its Articles of Incorporation to indemnify Directors and Officers, staff and agents (including volunteers) and to shield their personal assets from judgments in lawsuits for negligence.

Is encouraged to carry public liability insurance. To limit liability of volunteers, a sponsoring organization should consider public liability insurance coverage. Washington State law, RCW 4.24.670 Volunteer Liability, is representative of how a volunteer of a nonprofit organization or governmental entity may not be personally liable for harm caused by an act or omission of the volunteer as long as they are performing within the scope of their duties. Harm cannot have been caused by willful or criminal misconduct, gross negligence, reckless misconduct, or a conscious, flagrant indifference to the rights and safety of the individual harmed by the volunteer.

Mission Statements, Goals, and Objectives

It is important to clearly identify the values and vision of the volunteer driver program in a written mission statement. Goals and objectives are then needed to successfully carry out the program’s mission. The following guidance has been adapted for use by volunteer driver programs from the National RTAP’s Transit Manager’s Toolkit’s section on Mission and Leadership.

Mission statements describe what the program does for the community and should align with the vision of the sponsoring organization, as appropriate. A mission statement should define the program’s purpose in a concise, clear manner.

If a volunteer driver program and sponsoring organization do not have a written vision and mission statement, this is an opportunity to establish both statements through a collective process. To maintain effectiveness and to ensure they still align with the services the agency provides, mission statements should be reviewed periodically and updated, as necessary.

The process of creating a mission statement should be collaborative, but the writing of the statement should be led by one person. The following are characteristics of a strong mission statement:

- No longer than a few sentences

- Sixth grade level of comprehension

- Written in active voice

- Has few superlative adjectives or adverbs, if any

- Direct and honest

Mission statements should be reviewed for their effectiveness and validity. Keep these questions in mind:

- Is it relevant and current?

- Is it too difficult to understand?

- Will it inspire volunteers?

- Will it unify volunteers?

Examples of Mission Statements used by Volunteer Driver Programs:

- Chariot, Austin, Texas – “Chariot enriches lives and communities by providing transportation and socialization to non-driving seniors, helping them to age in place.” Read more about Chariot in Section 7: Case Studies.

- Neighbor Ride, Howard County, Maryland – “Neighbor Ride enhances the health and quality of life for Howard County’s seniors by providing the comfort and peace of mind of affordable, passenger-focused transportation services through a reliable, volunteer-based system.”

- Volunteer Transportation Center, Watertown, New York – “Provide transportation to health, wellness and critical needs destinations utilizing volunteers and mobility management for anyone who has barriers to transportation.”

Goals for a volunteer driver program might include coordination of volunteer resources (drivers), service design, service coverage (address mobility gaps, particularly in rural and underserved areas), program leadership and development, vehicles, equipment, maintenance, facilities, property, customers, communities to be served, marketing, financial viability, and sustainability (diversifying funding sources, including grants and community donations).

Objectives are needed to support program goals. Short-term objectives might include recruitment and retention of volunteers (maintain an active pool of trained and engaged volunteers), rider satisfaction, and low denial rates.

Rider Eligibility

It is crucial that volunteer driver programs decide who is eligible for the service and that they clearly communicate that information to potential riders and potential volunteers. Rider eligibility requirements are included with each case study in Section 7 - Case Studies.

For example, service eligibility may be based on:

- Age or disability status

- Lack of access to other transportation services

- Residency within the program’s service area

- Other factors (Some programs require that riders own or have access to a cell phone.)

It is crucial that volunteer driver programs decide who is eligible for the service and that they clearly communicate that information to potential riders and potential volunteers. Rider eligibility requirements are included with each case study in Section 7 - Case Studies.

For example, service eligibility may be based on:

- Age or disability status

- Lack of access to other transportation services

- Residency within the program’s service area

- Other factors (Some programs require that riders own or have access to a cell phone.)

To qualify for Chariot service, individuals must reside within the designated service area, be at least 60 years old, and feel uncomfortable driving. Read more about Chariot in Section 7 – Case Studies.

Limiting Financial Exposure Related to Risk

It is a common misconception that federal and state and volunteer protection laws protect nonprofits as well as volunteers. “Primary protection emanates from good management, personnel policies, and the regular assessment of your risks, a regularly updated risk management plan, and organizational policies and insurance coverages that address the needs identified by these processes.” (Risk Management and Insurance, Arizona State University (ASU) Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation.) A sponsoring organization will want to take steps to assure that it is protected from the unique risks posed by the operation of a volunteer driver program.

Waivers, Releases, Agreements to Participate, and Indemnification: These are all processes that a sponsoring organization, public or private, can use to limit and/or share program risks with riders and referring authorities. These procedures may be used when requested transportation is deemed to have special circumstances or risks. See the Risk section below for additional resources.

The information that follows is intended to assist new volunteer driver programs with a better understanding of the federal and state laws for nonprofits and volunteer liability.

Tips for Understanding Volunteer Insurance

The sponsoring organization’s insurance policies may also impact the volunteer’s insurance coverage. This is especially true for personal auto insurance policies. The insurer may provide coverage for volunteer drivers only when there is no reimbursement for expenses. See the article: Volunteer Driver Insurance in the Age of Ridehailing, AARP (2020) for more insight on difficulties that volunteer drivers may face with personal auto insurance policies. The sponsoring organization may want to consider a commercial general liability policy to cover volunteer drivers.

This list below has been adapted from Tips for Understanding Volunteer Insurance, Volunteers and Insurance Fact Sheet (2023) Wisconsin Office of the Commissioner of Insurance.

For Volunteers:

- Read your insurance policies to understand your coverage.

- Talk to your insurance agent or your insurer about any concerns you may have. Is there an issue related to reimbursement for expenses (gas, state inspections, etc.)?

- Shop around for coverage. While one insurance company may not cover your volunteer activities, other insurers may.

- Talk to the organization you will be volunteering for about insurance coverage. Is there a commercial auto insurance policy in place?

For Organizations:

- Read your insurance policies to understand what is and is not covered.

- Review your insurance coverage at least annually with your insurance agent. Have there been any changes to state coverage requirements?

- Make sure your policies and procedures line up with your insurance coverage.

- Before conducting any large public event, make sure you discuss coverage with your insurance agent or your insurer.

- Discuss any insurance issues with your employees and volunteers to make sure there is coverage in case of an unfortunate event.

The Volunteer Protection Act of 1997

The Federal Volunteer Protection Act of 1997 (VPA) was signed into law by Congress in 1997. The stated purpose of the VPA was to promote the interests of social service program beneficiaries and taxpayers and to sustain the availability of programs, nonprofit organizations, and governmental entities that depend on volunteer contributions. The VPA does not affect the liability of nonprofits and governmental entities with respect to harm caused by volunteer actions. 42 USC Section 14503 - Limitation on liability for volunteers provides certain protections from liability for volunteers serving nonprofit organizations or government entities for harm caused by an act or omission of the volunteer on behalf of the organization or entity if:

- The volunteer was acting within the scope of the volunteer's responsibilities in the nonprofit organization or governmental entity at the time of the act or omission;

- If appropriate or required, the volunteer was properly licensed, certified, or authorized by the appropriate authorities for the activities or practice in the state in which the harm occurred, where the activities or practice was undertaken within the scope of the volunteer's responsibilities in the nonprofit organization or governmental entity;

- The harm was not caused by willful or criminal misconduct, gross negligence, reckless misconduct, or a conscious, flagrant indifference to the rights or safety of the individual harmed by the volunteer; and

- The harm was not caused by the volunteer operating a motor vehicle, vessel, aircraft, or other vehicle for which the state requires the operator or the owner of the vehicle, craft, or vessel to-

- possess an operator's license; or

- maintain insurance. [42 USC Section 14503(a)]

With respect to state laws for nonprofits and volunteer liability, the VPA pre-empts any inconsistent law of a state, except if the state law provides more liability protection for volunteers than the VPA provides. (42 USC Section 14502 – Pre-emption and election of State non applicability) If the laws of a state limit volunteer liability subject to one or more of the following conditions, such conditions shall not be construed as inconsistent with 42 USC Section 14503 - Limitation on liability for volunteers:

- A state law that requires a nonprofit organization or governmental entity to adhere to risk management procedures, including mandatory training of volunteers.

- A state law that makes the organization or entity liable for the acts or omissions of its volunteers to the same extent as an employer is liable for the acts or omissions of its employees.

- A state law that makes a limitation of liability inapplicable if the civil action was brought by an officer of a State or local government pursuant to State or local law.

- A state law that makes a limitation of liability applicable only if the nonprofit organization or governmental entity provides a financially secure source of recovery for individuals who suffer harm as a result of actions taken by a volunteer on behalf of the organization or entity. A financially secure source of recovery may be an insurance policy within specified limits, comparable coverage from a risk pooling mechanism, equivalent assets, or alternative arrangements that satisfy the State that the organization or entity will be able to pay for losses up to a specified amount. Separate standards for different types of liability exposure may be specified. [42 USC Section 14503(e)]

State Laws for Nonprofits and Volunteer Liability

Prospective sponsoring organizations should be aware of the volunteer protection laws in their state and service areas. Examples of state volunteer protection laws are listed below.

- Arizona: Actions Against Volunteers, Qualified Immunity; Insurance Coverage (Ariz. Rev. Stat. 12-982).

- Arkansas: Arkansas Volunteer Immunity Act, (Ark. Code Ann. 16-6-102)

- Florida: Florida Volunteer Protection Act (Fla. Stat. 768.1355).

- Washington: Liability of Volunteers of Nonprofit or Governmental Entities (Wash. Adm. Code 4.24.670).

- Wisconsin: Limited Liability of Volunteers (Wis. Stat. 181.0670)

Note: At the time that the Volunteer Protection Act of 1997 was drafted, all states had enacted laws related to Volunteer Liability.

What Type of Insurance is Needed?

As described in the previous section, insurance is an important part of limiting the financial exposure due to the risks associated with operating a passenger transportation program. Some states have specific provisions or requirements for the types and levels of coverage that nonprofit agencies, including volunteer driver programs must have in place. As examples:

Arizona: Actions Against Volunteers, Qualified Immunity; Insurance Coverage (Ariz. Rev. Stat. 12-982). Arizona law provides that the liability of the insurance carrier with respect to the insured and any other person using the vehicle with the express or implied permission of the insured shall extend to provide excess coverage for a nonprofit corporation or nonprofit organization for the acts of the operator in operating a motor vehicle at all times when the operator is acting as a volunteer for that nonprofit corporation or nonprofit organization.

Washington: Private, Nonprofit Transportation Providers, Insurance (Wash. Adm. Code 480-31-070) Washington law provides that the combined bodily injury and property damage liability insurance or surety bond must not be less than: Five hundred thousand dollars combined single limit for vehicles with a passenger capacity of less than 16 passengers, including the driver; One million dollars combined single limit for vehicles with a passenger capacity of 16 or more passengers, including the driver.

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations should consider the information below when deciding what type and level of insurance they should carry. Nonprofit organizations are encouraged to research and find experienced and trustworthy insurance advisors (agents or brokers) to work with in determining risk associated with operating a volunteer driver program. Volunteer driver programs should also plan to review insurance coverage on an annual basis or as recommended by their insurance advisor. Also see the Risk Management in this section of the Toolkit.

Unless otherwise noted, the following list is adapted from Washington State’s original Volunteer Driver Program Guidebook, the Nonprofit Risk Management Center’s article: What Basic Insurance Coverage Should a Nonprofit Consider?, and the Wisconsin Office of the Commissioner of Insurance’s Volunteers and Insurance Fact Sheet (2023).

Liability Insurance

Liability insurance protects the sponsoring organization from claims alleging negligent conduct by the nonprofit, or its employees, volunteers or agents. Public liability insurance is also discussed earlier in this section.

Comprehensive or Commercial General Liability

Comprehensive or commercial general liability (CGL) coverage may include, but is not limited to, contractual liability, products and completed operations, property damage, and employer's liability. Names of individuals insured should include directors and officers, employees, representatives, agents, and volunteers. Properly structured, this coverage will include employment practices, errors and omissions, directors and officers, and volunteer's personal liability.

CGL policies cover claims against:

- Bodily injury (someone suffered an injury)

- Property damage (someone’s property was damaged)

- Personal injury (offences for libel, slander, defamation, or malicious prosecution)

- Advertising injury (libel, slander, or copyright infringement due to advertising activities)

A CGL policy may also include medical expense that provides a low limit (usually $5,000 or $10,000 per person) for “no-fault” bodily injury. Recommended coverage should be set at a minimum $1 million for each incident.

Business Auto Liability

The volunteer's own automobile insurance is primary. The volunteer driver program or sponsoring organization's business auto liability would be secondary. Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations should be sure that their policy covers non-owned and for hire vehicles. Generally, this policy would be in equal million dollar limits. Business auto coverage for any auto at no less than $1 million each accident is recommended. As an example, all Washington State non-profit transportation providers are required to have coverage of $1.5 million.

If the sponsoring organization or volunteer driver program owns vehicles, a business auto policy would be necessary to cover the vehicles for auto liability and physical damage.

The Nonprofit Risk Management Center’s article, Risk on the Road: Managing Volunteer Driver Exposures discusses the difference between insurance coverage when a volunteer drives their own car and when a volunteer drives a vehicle owned by a nonprofit organization.

Umbrella/Excess Liability

An umbrella or excess liability policy provides the organization with additional policy limits for a catastrophic liability loss. The umbrella policy provides additional limits over the general liability, business auto liability, and employers liability policies. General liability and auto liability can be included under the umbrella. Many non-profit organizations are currently carrying $5 million of umbrella excess liability coverage.

Directors and Officers Liability Insurance

If not covered by general liability insurance, directors and officers (D&O) coverage or errors and omissions (E&O) coverage can be purchased. This coverage should include liability due to employment practices, which can involve treatment of volunteers. Included in the coverage can be all past, present and future directors and officers, employees, volunteers, trustees, committee members, and the entity itself.

Volunteers' Liability Insurance

As an alternative to, or in addition to other existing liability coverage, the Sponsoring Organization should consider participating in a volunteers' liability insurance program. This insurance typically provides coverage for medical treatment when the volunteer is injured during their volunteer services.

Property Insurance

A commercial property policy covers the property (furniture, fixtures, office equipment, stock, etc.) that the owned by the sponsoring organization. If the volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organization owns any computers or electronic equipment, a computer and cyber security insurance policy may be worthwhile.

Volunteer/Employee Dishonesty

This insurance covers theft of funds and/or supplies by volunteers or staff. Most organizations will already have this coverage, sometimes called "bonding." Policies should be checked to insure each volunteer even though the risk may be low.

Medical Insurance

It is important that volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations recognize that vehicle insurance does not cover injuries that may happen while the volunteer is involved in activities separate from operation of the vehicle. Many volunteers are retired persons who may have inadequate or no medical insurance coverage.

Risks to the volunteers can be covered by a variety of methods. Medical or accident insurance provides excess accident medical coverage directly to a volunteer when he or she is injured traveling directly to or from, or participating in, volunteer activities. If Medicare covers the volunteer, the coverage would be in addition to that coverage. If the volunteer has no other coverage, the policy would be primary.

Risk Management

Insurance coverage is not the only way to manage risk. Understanding risk and engaging in risk management activities is important for sponsoring organizations and volunteer driver programs. The processes involved in identifying and managing risks can protect the sponsoring organization and its programs from harm while creating opportunities to improve a volunteer driver program’s performance. See Section 7 -Case Studies/Common Themes/Risk Management Strategies for more thoughts, ideas, and solutions related to the subject of Risk Management.

The National Council of Nonprofits is a good resource for organizations that need help understanding the types of coverage that are available and most appropriate for volunteer driver programs and supporting organizations. See the National Council of Nonprofits’ Running a Nonprofit. Also, Cybersecurity for Nonprofits.

As an introduction to risk management for nonprofits, the Nonprofit Risk Management Center (NRMC) website includes the following articles:

- Take Action on Risk: Make a Plan, Not a List - NRMC-Risk-Management-Essentials-Fall-2022-Newsletter. This article discusses a variety of approaches to risk action planning. An “Action Planning” worksheet is included.

- Transporting People: What to Consider - NRMC-Risk-Management-Essentials-Summer-2023-Newsletter. This article speaks to risk management as it pertains to drivers, including volunteer drivers.

The Nonprofit Risk Management Center published two documents in 2009 that that clearly explain what the Volunteer Protection Act does. Both documents include valuable information and examples of state volunteer protection and liability laws and cases. Volunteer Protection Act – Ten Years Later, October 2009 and State Liability Laws for Charitable Organizations and Volunteers.

The Nonprofit Risk Management Center’s article, Risk on the Road: Managing Volunteer Driver Exposures in addition to the discussion on volunteer driver insurance coverage refer to above, this article also includes guidance on risk management specific to volunteer drivers and a sample volunteer driver pledge.

Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources (GWaar): Volunteer Driver Insurance infographic 10-2023.

Post Sedation Transportation

Volunteer driver programs may be asked to provide rides for medical procedures that require a “responsible party” to accompany the patient home. Programs often struggle with the liability related to post sedation transportation. Volunteers, unless specifically trained to do this, should not be put into this situation and should not sign or have their name put down as the “responsible party.” Section 7 -Case Studies/Common Themes/Medical Considerations compiles shared ideas and potential solutions related to client safety, training, and support for medical appointments.

While this Toolkit does not have a definitive answer to this difficult issue, we encourage the reader to review the King County Mobility Coalition and the Eastside Easy Rider Collaborative’s memo on The Need for Medical Chaperones for Post-Sedation Transportation. The memo summarizes the groundwork for piloting a medical chaperone project that would provide volunteers to accompany isolated older adults to and from medical appointments involving sedation when a “responsible party” is required post-procedure for patient safety. The memo’s list of recommendations for a successful medical chaperone pilot has been adapted below:

- Use a cross-sector approach involving both healthcare and transportation.

- Partner with an organization that has a volunteer base in place, such as Eastside Friends of Seniors or Catholic Community Services. Volunteers are an important factor given that for-profit caregivers are cost-prohibitive for many isolated, older adults in our community. Additionally, an existing volunteer base provides previously established, trusted relationships.

- Organizations need to consult with their current insurance company to inquire about adding liability coverage for volunteers.

- Develop a waiver specific to participation in the medical chaperone program that addresses insurance liability concerns.

- Consider partnering with a personal emergency alert system. A temporary device can augment and extend the supervision provided by a volunteer.

- Funding sources may be available through cities and organizations such as Community Care Corps. Healthcare facilities may also be a potential funding source, given that they will benefit from medical chaperone volunteers, which would result in fewer appointment cancellations.

- Offices of Health Equity at healthcare settings may offer connections for information and potential funding sources. • Consider including stipends for volunteers in a proposed budget.

- Trusted Riders is one possible resource for training and credentialing of volunteer medical chaperones.

- Start small, with one healthcare facility and one procedure, then scale up.

- Review the study, Outpatient Dismissal With a Responsible Adult Compared With Structured Solo Dismissal: A Retrospective Case-Control Comparison of Safety Outcomes.

The Importance of Community Relations

The drivers for the Sponsoring Organization will influence the opinion and image that people in the community have of the Sponsoring Organization. The way each volunteer driver performs their duties will contribute, either favorably or unfavorably, to the Sponsor's image. Drivers are also the best sources of information for management about how services are received in the community. The reality of providing public transportation service is that the public expects proficient driving; they take good performance for granted, and are quick to complain about poor performance.

Community Outreach

Well-defined and communicated policies can assist with public perception. Here are examples of volunteer driver programs that have easy to access policies on line and have also used social and local media to make get the word out about their programs.

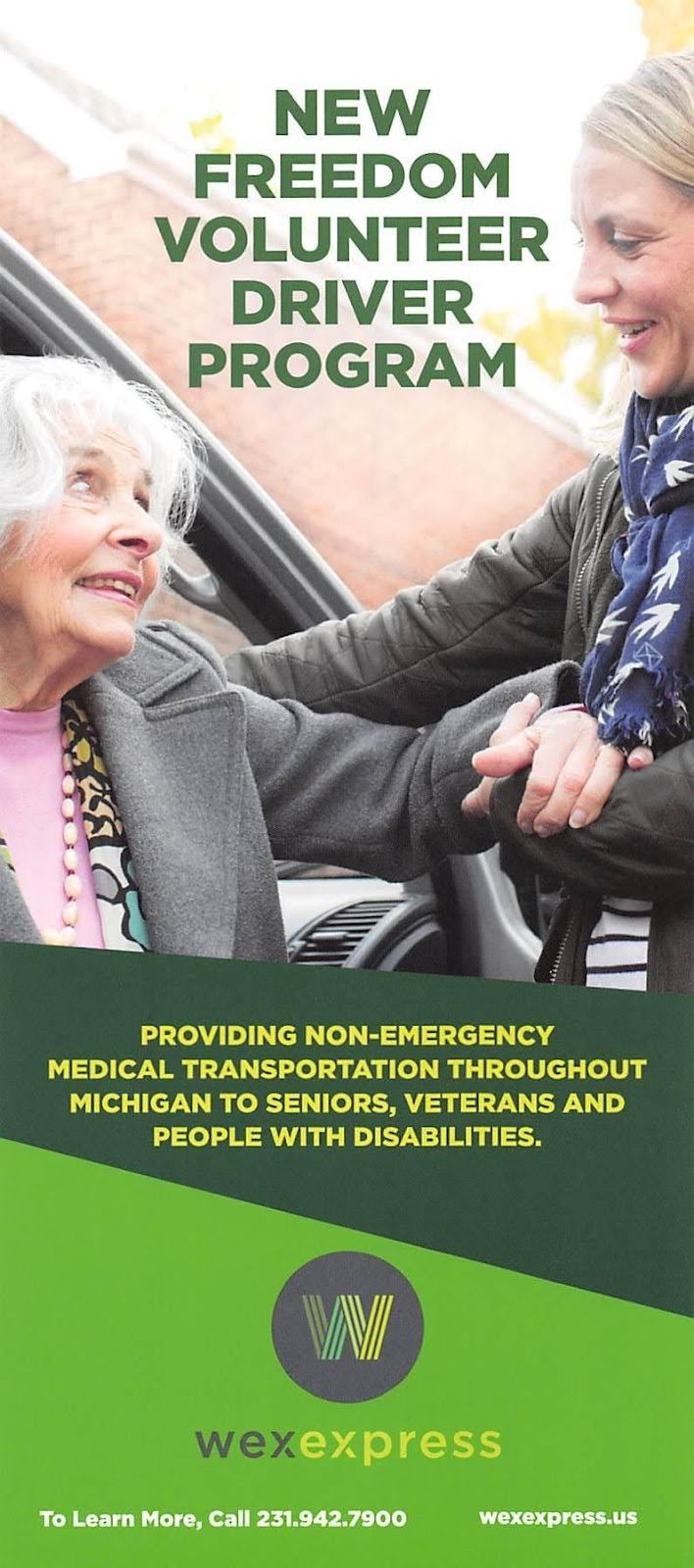

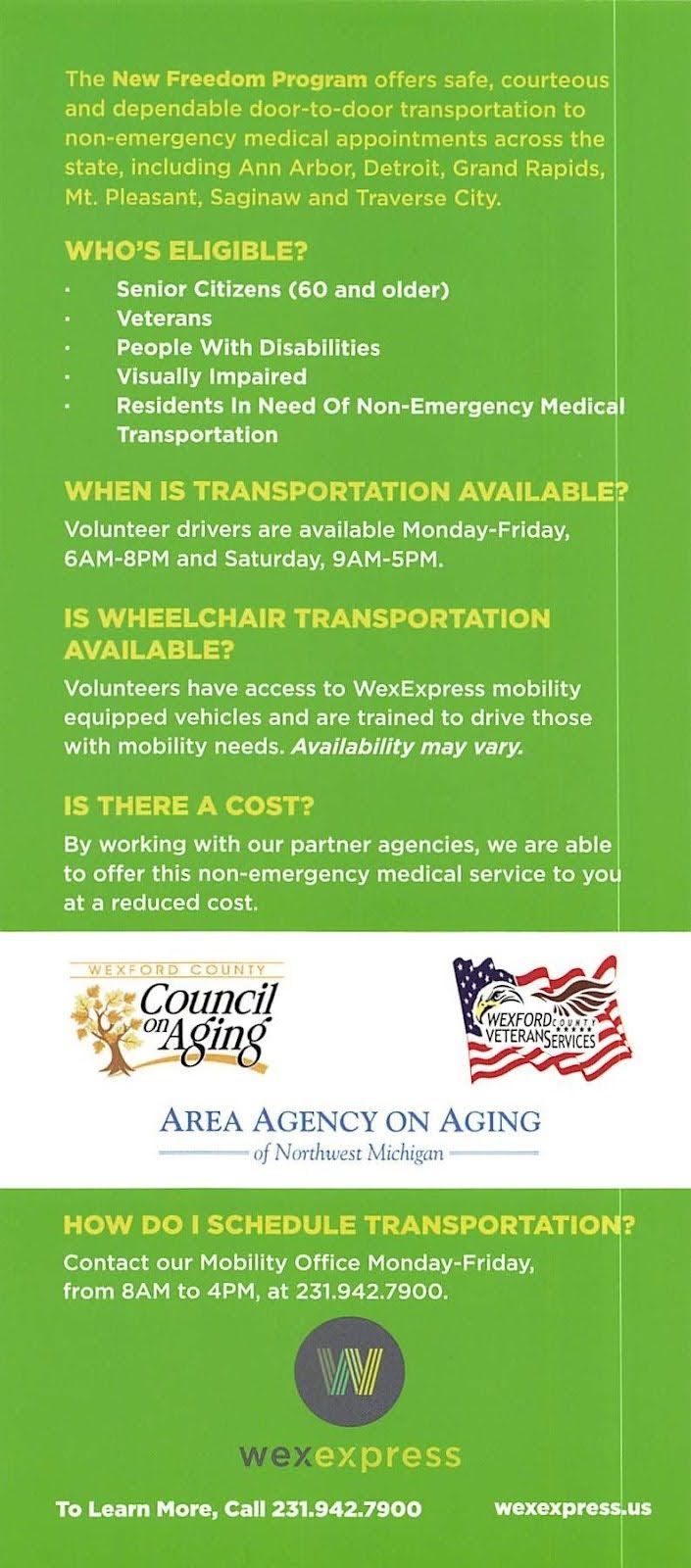

- WexExpress New Freedom in Cadillac, Michigan offers the following outreach messages - Rider Resources, Mobility Coordination Services, Become A Volunteer, Local News Coverage Video: The New Freedom Volunteer Driver Program Introduced On the four.

- King County Metro Community Van in Seattle, Washington launched a coordinated awareness campaign in 2021 to promote volunteer driving. This initiative included the development of a Rider Guide and a Volunteer Guide to assist new participants. HopeLink Community Van Rider Guidelines and Welcome Packet.

- Chariot in Austin, Texas includes a video on their website, Chariot Movie: formerly Drive A Senior Central Texas 2022, that features a song recorded by a local musician.

Marketing

Marketing is a critical component to the success of any volunteer driver program. Many volunteer driver programs produce their own recruitment and advertising materials for the purposes of recruiting both new riders and volunteers. In some cases, marketing materials may also be helpful in educating medical and other service providers about the sponsoring organization’s association with the volunteer driver program. WexExpress’ partnership with Dynamic Physical Therapy in Cadillac, Michigan is an example of a very successful community partnership that also resulted in a great marketing opportunity.

Marketing materials may also be used to advantage when engaging with potential financial sponsors. It is important to remember that marketing will be different if you are advertising to potential riders or to potential volunteers.

A key element of marketing for all volunteer driver programs is messaging that resonates with volunteers - like the benefits of volunteering.

- SAINT in Fort Collins, Colorado uses an online webpage that includes requirements and skills needed, a description of Saint’s program, and information on how to apply. Drive for SAINT

- Chariot in Austin, Texas uses an online webpage that explains volunteer driver eligibility requirements, the program’s service area, and how the program work for volunteers who drive their own vehicles. Chariot Volunteer Application Form

- Driver recruitment efforts for Ride Connection in Portland, Oregon include outreach fairs, presentations at senior centers and civic organizations, newspaper ads, radio station advertisements, and word-of-mouth referrals.

Volunteer driver programs will want to have a variety of informative and easy-to-use materials to help riders use the service.

- SAINT in Fort Collins, Colorado describes rider eligibility, helps riders register, and explains how the service works (service area maps, scheduling, riding, and cost) online. Free Senior & Disabled Transportation Services – Ride with SAINT.

- Chariot in Austin, Texas describes rider eligibility, enrolls riders, and describes the program’s services and service area online. Request Individual Rides, Request Community Rides.

As appropriate, attention should be paid to ensuring that materials are provided in languages other than English and be in accessible formats. QR codes may also be used to assist riders and possible volunteers in downloading the information. Materials to consider include:

- A volunteer driver program webpage on the sponsoring organization’s website with additional resources for riders and volunteers

- Flyers, posters, and rack cards (see WexExpress New Freedom’s rack card below) to explain the service and provide links to the sponsoring organization or volunteer driver program’s website

- FAQs to help explain how to volunteer or request a ride, and pricing

- Grab-and-go business cards with the volunteer driver program’s phone line and QR code

See more on the topic of Communication with Riders/Information Accessibility in

Section 3: Important Information About Riders.

Branding

Branding and marketing enhance public awareness and volunteer recruitment. Branding a volunteer driver program will help differentiate it from other transit services in the area. There are various strategies to consider.

The following considerations for developing a brand have been adapted from the Texas Department of Transportation’s Texas Rural Microtransit Guidebook, Develop a Branding, Marketing and Outreach Plan:

- Service name or nickname – This is the name most people will use for the new service. Choose a recognizable and relatable name. Perhaps have a contest among students, combined with a full rebrand celebration. The new name should:

- Be easily recognizable or catchy

- Identify with the service – Such as “Volunteers in Motion” or “Chariot”

- Avoid acronyms

- Vehicle colors and paint scheme – Eye-catching vehicles that will be noticed and can instill pride in the new service. Is there a bright local color that symbolizes the area?

- Decals for privately owned vehicles may also be considered to identify them as a part of the volunteer driver program. Volunteers should check with their insurance carrier to ensure that there are no concerns.

- Use flyers, social media, and local media coverage to reach both riders and potential volunteers. Examples of marketing materials, flyers and posters, used by these volunteer driver programs and supporting organizations are included in the appendix to Section 7: Case Studies.

- Bring in system sponsors – Having sponsor names on the sides of the vehicles, perhaps in a corner, can lend credibility to the system.

- Corporate Sponsorship – Explore partnerships with local businesses (e.g., grocery stores, medical facilities) for financial support.

- Establish a website and social media presence – At a minimum, the website should include an introduction to the program’s transportation services, information on how to ride, and information on how to become a volunteer. Many websites also include a program history, forms, newsletters, and access to annual reports. Each of the volunteer driver programs included in Section 7: Case Studies has a website, webpage, or other social media.

Additional Resources

Policies and Procedures

Policies and procedures are essential to the successful operation of any transit system, including volunteer driver programs. Policies and procedures should be written and made readily available to all staff, both paid and unpaid. While not all personnel and organizational standards apply to volunteers, it is important that the program’s policies and procedures be clearly defined for everyone. In some cases, it may be necessary to require that volunteers acknowledge understanding of certain policies in writing, as well. However, care should be taken to strike a balance between the needs of the sponsoring organization and the nature of volunteering and the volunteer perspective.

In addition to guidance and information about organizational and personnel policies and procedures, this section of the Toolkit also contains important information and resources about how to develop policies and procedures that may be needed in the event of an emergency or crisis.

Organizational Policies

Many funding agencies require sponsoring organizations (and stand-alone volunteer driver programs) to have specific written policies in place that apply to volunteers as well as paid employees. All programs should check with their funding agencies to determine what policies are required and, in some cases, which programs are not allowed to accept donations from passengers (example: Medicaid Non-Emergency Medical Transportation).

This list of recommended program policies was included in the original Washington State Volunteer Driver Program Guide and has been updated and expanded to include policies required or recommended by other sources, as noted. One such source is the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT). MoDOT‘s List of Recommended Policies for Volunteer Driver Programs, IN TRANSIT, March 2024) has been adapted for use by a national audience in the list below.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Volunteer driver program and supporting organizations will need to have policy in place to ensure that the services provided are in compliance with Title III of the ADA. For example, if the volunteer driver program operates under the sponsorship of a federally funded public transportation provider, the types and modes of other transportation services that are operated by the supporting organization mut be taken in to consideration. A volunteer’s privately owned vehicle may not be appropriate to transport persons with certain disabilities because it is not wheelchair accessible. Those persons may need to be referred to appropriate alternate service providers.

All volunteer drivers should be trained to proficiency in the requirements of ADA. Training should include service animals, securing mobility devices (as appropriate), and sensitivity to people with disabilities.

National RTAP’s ADA Toolkit and the FTA’s Americans with Disabilities: Guidance website are both recommended resources for ADA compliance related questions. In addition to information meant to help public transportation providers comply with ADA regulations, National RTAP’s ADA Toolkit also includes many other ADA related topics and resources including service animals, rider assistance and customer service, driver training, and examples of suggested practices.

Ethics

Volunteers should be included in the agency’s Code of Ethics, the set of principles or concepts that reflect the volunteer driver program and sponsoring organization’s core values.

Code of Conduct

A Code of Conduct for volunteer drivers should include specific behavioral rules and guidelines, expectations for respect and treatment of all staff, clients and community members, as well as service requirements.

Drug-Free Workplace

In accordance with 41 U.S.C. Section 8103 - Drug-free workplace requirements for Federal grant recipients, Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations that receive federal funding are required to comply with the Drug-Free Workplace Act. This means that the volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations must have a policy that prohibits employees and volunteers from the unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensing, possession or use of a controlled substance at any of the sponsoring organization’s facilities and/or during any of the programs offered by the sponsoring organization.

Drug and Alcohol Testing

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations that receive federal funding should work with their funding agency to ensure compliance with drug testing policies and procedures.

Drivers, including volunteers, of vehicles that have been manufactured to transport 16 or more passengers, including the driver, must have a valid commercial driver’s license (CDL) with a passenger endorsement. Drivers holding a CDL must be included in a drug and alcohol testing program that complies with U.S. Department of Transportation regulations at 49 CFR Part 40 - Procedures for Transportation Workplace Drug and Alcohol Testing Programs.

49 CFR Part 655.4 - Prevention of Alcohol Misuse and Prohibited Drug Use in Transit Operations, defines a volunteer as follows: "A volunteer is a covered employee if: (1) The volunteer is required to hold a commercial driver's license to operate the vehicle; or (2) The volunteer performs a safety-sensitive function for an entity subject to this part and receives remuneration in excess of their actual expenses incurred while engaged in the volunteer activity."

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations that receive federal funding are also required to comply with the Drug-Free Workplace Act. Sponsoring organizations must have a policy that prohibits employees and volunteers from the unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensing, possession or use of a controlled substance at any of the sponsoring organization’s facilities and/or during any of the programs offered by the sponsoring organization. To better understand FTA drug and alcohol regulations at 49 CFR Part 655, recipients or subrecipients of Sections 5307, 5309 or 5311 federal funding are encouraged to visit the FTA’s Drug and Alcohol Program website. This website also includes 5310 Funding Frequently Asked Questions.

National RTAP’s Substance Abuse Awareness Training, Testing, and Compliance Technical Brief, updated in 2022, is a helpful resource with information about the requirements, including frequently asked questions and links to a host of federal regulations and resources. National RTAP’s Transit Manager’s Toolkit/Drug and Alcohol Programs section is also a good resource for Drug and Alcohol Testing Program compliance related questions.

Section 4: Establishing and Managing a Volunteer Driver Pool also includes helpful information about Commercial Driver Licenses.

Harassment

A volunteer driver program should have a policy that it will not tolerate verbal or physical conduct by any employee or volunteer which harasses, disrupts or interferes with another’s work performance or which creates an intimidating, offensive or hostile environment.

Confidentiality

Transportation volunteers often know or become familiar with riders. While it is desirable to establish a positive relationship with riders, it is important to avoid situations that can create “Conflicts of Interest.” A recommended practice is to have volunteers read and sign the confidentiality policy annually.

Reporting Suspected Abuse

This typically applies to serving vulnerable adults and children, based on state and federal legal requirements.

Supervision of Volunteers, including Annual Reviews

The volunteer driver program and supporting organizations should have a policy in place that clearly describes how volunteer drivers are supervised.

Section 4: Establishing and Managing a Volunteer Driver Pool/How to Select Drivers contains more detailed guidance and information related to Volunteer Driver Selection Practices, Organizational Standards, and Personnel Actions.

Non-discrimination

Volunteer drivers are the face of the program. Expectations for respect and treatment of all paid and unpaid (volunteer) staff, clients and riders, and other community members, as well as for the agency or program’s service requirements should be clearly documented in policy.

Payment and Donation Policies

The following information should be considered when developing and implementing Payment and Donation policies.

- Copies of the volunteer driver program and sponsoring organization's payment and donation policies should be made available to volunteers driving personally owned vehicles and copies should be posted in agency owned vehicles. The policies should also be included in brochures and advertising materials.

- Programs should design a system that respects the individual's anonymity. Some volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations request support from the community and the riders in the form of donations, yet do not pressure those who cannot afford to pay.

- Drivers should be well informed about the donation policy. It is not appropriate for drivers to demand donations from riders.

- Many riders prefer to pay or make a donation to the volunteer driver program or sponsoring organization once a month rather than make a donation each time they ride.

- In order to avoid misunderstandings and protect the rider's anonymity, a collection system that does not require drivers to handle cash is preferred.

- When the volunteer driver program or sponsoring organization plans recreational trips outside of regular service hours, it may be appropriate to charge riders a fare in order to recapture some of the costs associated with the trip. However, care must be taken to ensure compliance with all funding sources.

Reimbursing Volunteers

Most volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations reimburse volunteers for mileage and other authorized expenses. The program should have a form to be used by personally owned vehicle (POV) volunteers to document mileage and other expenses.

According to the Rural Health Information Hub (RHIhub), “Rural communities have implemented three types of reimbursement strategies for volunteer driver models: Volunteering without reimbursement, trip/time banking, and mileage reimbursement.” The three strategies are summarized below and may be accessed in more detail on the RHIhub’s Volunteer Models for Rural Transportation website.

Volunteering Without Reimbursement for Time or Mileage - Volunteer drivers contribute their time, drive their own vehicles, and provide their own gasoline without reimbursement.

Trip Banking/Time Banking - Volunteer drivers contribute their time without reimbursement and bank the time they spend providing services. Some programs allow volunteers to exchange hours driven (banked) for other goods or services, like housekeeping or financial services.

Volunteer Mileage Reimbursement Programs - Volunteer drivers track their mileage to receive reimbursement. Some programs may reimburse in accordance with the government's mileage reimbursement rate, while others may pay volunteers per trip, up to a limited amount, or with non-monetary incentives.

The National Council of Nonprofits encourages all nonprofits to be familiar with the employment laws in the state(s) where the nonprofit operates. State associations of nonprofits frequently offer educational programs and reliable resources related to managing employees and volunteers.

Note: IRS regulations may allow for deduction of volunteer expenses if not reimbursed by sponsoring agency.

Persons with Disabilities Parking Privileges

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations may be able to apply for persons with disabilities special license plates and placards if they meet individual state criteria. Here are some examples:

- Washington – Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations that meet Washington State’s criteria at RCW 46.19.020 for Eligible Organizations can apply to the Washington State Department of Licensing for persons with disabilities special license plates and placards. Organizational Application for Disabled Person Parking Privileges

- Connecticut – An organization that transports persons with disabilities can request a special placard online from the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles. A qualifying organization must use a vehicle at least 50% for daily transport of qualifying persons with disabilities.

- Florida – Section 320.0848(1)(e), Florida Statutes, allows for the issuance of a persons with disabilities parking permits to any organization demonstrating a bona fide need. Organizations providing regular transportation service to persons with mobility impairments, or those certified as legally blind, may be issued one parking permit for each vehicle registered in the name of the organization, with a valid registration. Florida Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations should have policy on the use of persons with disabilities plates and placards. Those policies should consider the following:

- Persons with Disabilities parking privileges (permits, placards, and license plates) may only be used while providing transportation to persons with disabilities. Sponsoring Organizations should develop policies regarding appropriate use of the placards and permits including a requirement for their return when a volunteer is no longer registered with a program.

- Volunteers should be trained on the use of persons with disabilities plates and placards.

Sponsoring Organizations may be required to report on the status of each permanent persons with disabilities parking placard or persons with disabilities special license plate on a regular basis depending on individual state laws.

Emergency Management

Volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations are encouraged to have policy and procedures in place in the event of an emergency incident. It is also a good practice for transit agencies, including volunteer driver programs, to be involved in planning local emergency response plans and procedures. Transit agencies, including volunteer driver programs, are often able to provide state and local emergency management officials with much needed information about how to reach vulnerable populations in times of crisis.

The Emergency Management section of National RTAP’s ADA Toolkit includes information and resources that will be of value to volunteer driver programs and supporting organizations seeking to develop an emergency response plan with local emergency management agencies and other stakeholders.

National RTAP’s Emergency Information Dissemination Technical Brief focuses on being prepared to work with the public, community leaders, and the media in an emergency. Two case studies are included in this brief that volunteer driver programs may learn from: Crawford Area Transit Authority (CATA) describes working to help its community through a fierce winter snowstorm and Central Oklahoma Transit System (COTS) details the process of providing services in the aftermath of a large tornado.

The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) Standards Development Program, Emergency Communication Strategies for Transit Agencies (Revised February 2020) contains standard measures that transit agencies, including volunteer driver programs, would use to prepare in advance for an emergency incident.

The list that follows is adapted from the APTA Standard and is meant to give volunteer driver programs and supporting organizations an idea of the different types of incidents that they should work with their local and state emergency management authorities to prepare for:

- Terrorist attacks

- Natural disasters

- Rider, volunteer, and employee safety or security issues

- Mass casualty incidents

- Catastrophic equipment failures or defects

- Power failures or blackouts

- Incidents resulting in evacuation or rescue from transit vehicles or stations

- Any other incident causing major service disruptions and necessitating notification and timely, accurate updates to riders, employees and volunteers, and the public

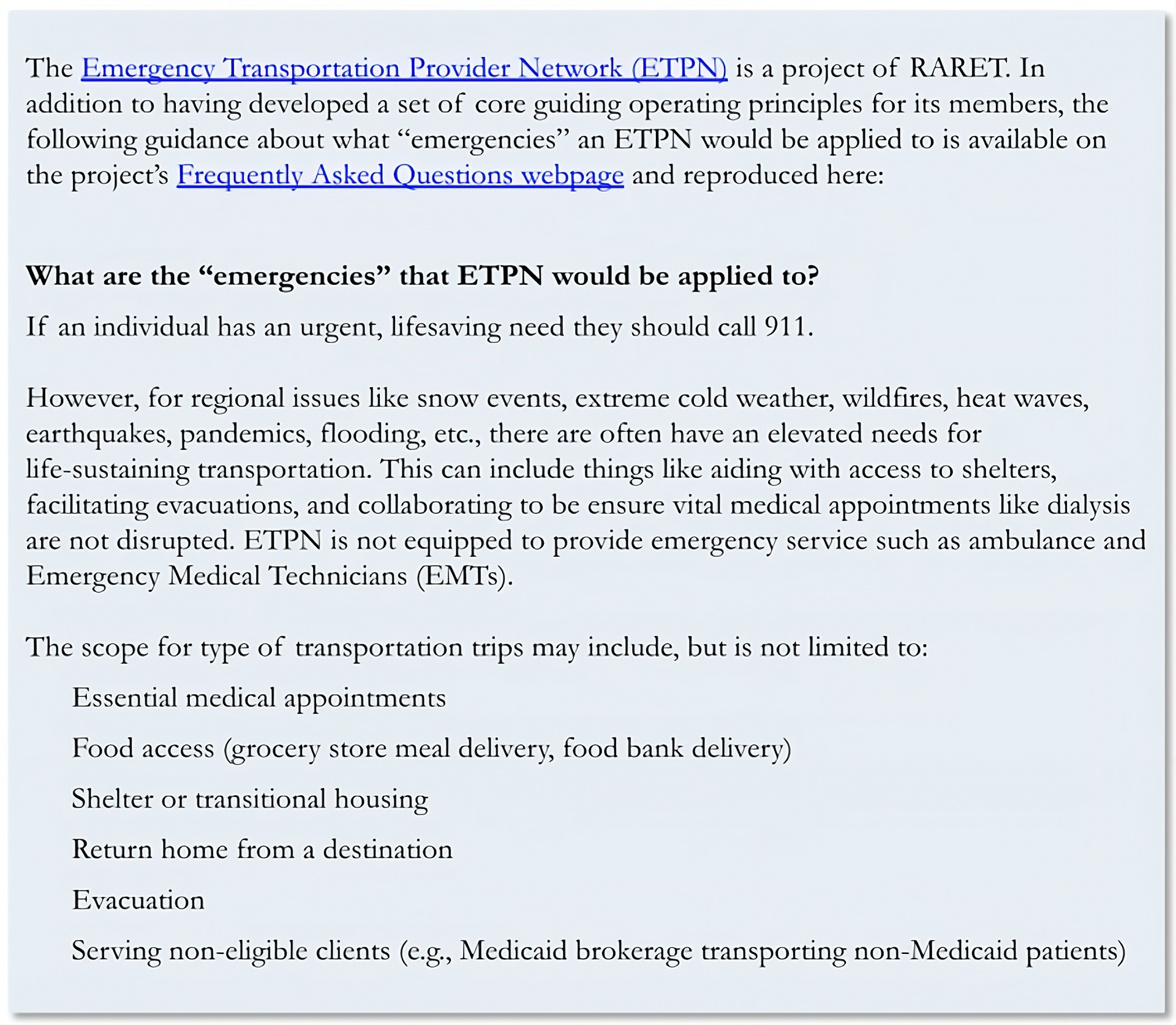

The Regional Alliance for Resilient and Equitable Transportation (RARET) is a workgroup composed of emergency managers, transportation providers, human service agencies, and community advocates representing King, Pierce, and Snohomish Counties in Washington State. Current efforts include convening regional partners to identify opportunities for collaboration and resource sharing, building a network of transportation providers able to operate in an emergency, and identifying the transportation needs faced by populations with access and functional needs in a regional emergency.

RARET hosts an annual tabletop event in King County Washington. The workgroup is piloting key strategies to increase the critical transportation services available to populations with access and functional needs including older adults, people with disabilities, English-language learners, and others in the event of an emergency in the Puget Sound region.

RARET has developed the following strategies to increase the critical transportation services to populations with access and functional needs in the event of an emergency:

Strategies

- Gap Analysis: Identify what and where the gaps are in transportation for vulnerable populations before, during, and after an emergency.

- Coalition Building: Support and strengthen partnerships between transportation providers, emergency managers, human service agencies, and vulnerable populations.

- Preparedness: Ensure the supply (providers/organizations) and demand (riders) are as prepared as possible to operate or function during an emergency.

- Resource Identification: Assess and distribute information about the availability of transportation resources in an emergency.

- Coordination: Develop a coordinated network to operate in an emergency.

- Communication: Ensure the coordination network and demand of transportation in an emergency is clearly communicated and comprehended by all relevant stakeholders.

Additional Reading:

RARET and ETPN pages on the King County Mobility Coalition website. Emergency Transportation Provider Network (ETPN) Guiding Principles

RARET's coalition-based model: Addressing complex life-sustaining transportation during emergencies (Dean Syndor) is available on the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine website. This paper discusses the work of RARET and the development of an emergency transportation provider network (ETPN). Methods to adapt RARET/ETPN model to other jurisdictions are suggested in the paper.

Personnel

A personnel policy manual is the best way to define and explain manager, employee, and volunteer relationships, present legal requirements, and outline expectations for a positive work atmosphere.

New personnel manuals and any revisions should always be reviewed by the volunteer driver program or sponsoring organization’s legal counsel and approved by its governing board. Volunteer driver programs that are part of a local or Tribal government should also refer to that government’s personnel policies.

While National RTAP’s technical brief: Developing and Maintaining a Transit System Personnel Policy is not expressly written for volunteer driver programs, it does contain valuable information and guidance that may be of use to new programs. The following is adapted from the National RTAP brief and is a list of major topics and policies that are often covered in a personnel policy manual:

- Mission Statement – A short statement identifying the reason that the organization or VDP was created.

- Statement of Purpose – A statement to explain the purpose of the manual. For example, “to establish a uniform system of personnel policies within the organization and to outline procedures governing the behavior of all employees and volunteers”)

- Volunteer Driver Selection Practices – Describe the practices and procedures involved in selecting volunteers. Include specific qualifications, driving history requirements, and details about the selection process itself (application, review and interview processes, criminal history checks, proof of insurance, etc.). See Section 4: Establishing and Managing a Volunteer Driver Pool/How to Select Drivers/Driver Selection.

- Volunteer Status – Include volunteer categories, classifications and job descriptions.

- Attendance – Hours of work, absenteeism, and punctuality.

- Reimbursement – The organizations policies on reimbursement of expenses like mileage and gasoline.

- Benefits – As an example, some VDPs offer assistance with other services that the Sponsoring Organization provides to members.

- Organizational Standards – The following is a list of topics and organizational policies that would be appropriate for inclusion in this section of the manual.

- Policies on Substance Abuse

- Harassment

- Standard of Dress

- Code of Ethics

- Code of Conduct

- Use of Agency Vehicles

- Political Activity

- Media Contact

- Release of Information

- Smoking

- Computer/IT/Internet

- Social Media

- Reporting Suspected Abuse (Neglect, Abandonment, and Exploitation)

- Incident Reporting to include both motor vehicle accidents and other incidents involving a rider (falls, seizures, self-neglect or abuse).

- Privacy Rights

- Personnel Actions - The following is a list of topics that would be appropriate for inclusion in this section of the manual. See Section 4: Establishing and Managing a Volunteer Driver Pool.

- Training and Development

- Performance Evaluations

- Driver Review

- Driver Suspension or Termination

- Intervention

- Exit Interviews

- Medical Restrictions

- Grievance Procedures

- Documentation and Archiving Practices for Volunteer Personnel Files

Importantly, organizational policies, whether included in a personnel policy manual or not, must be provided to all volunteers. National RTAP’s technical brief: Developing and Maintaining a Transit System Personnel Policy recommends conducting an in-person orientation, either one-on-one or in a group, and obtaining a signoff to verify receipt of the manual. Major revisions to the manual, including the addition of new elements, would necessitate additional orientation and signoff.

Need More Information, Examples, or Resources?

Section 8 – Model Forms (Templates), Policies, and Procedures contains model forms (templates), policies, and procedures that are composites of similar forms, policies, and procedures used by many of the contributing volunteer driver programs. The materials can be freely downloaded and edited; however, some forms should be reviewed by your legal counsel to ensure compliance with state and local laws and for liability purposes.

The

Appendix to Section 7 – Case Studies also contains examples of the forms, policies, and procedures used by many of the volunteer driver programs that are included as case studies in this Toolkit.

Funding

Sponsoring Organizations should carefully weigh the contractual requirements of available funding sources. Sponsoring Organizations should check with their funding agencies to verify all of the requirements that apply to volunteer driver programs.

Many funding sources allow volunteer driver programs to use volunteer time as match, making it easier to secure funds that require a local match than a typical paid operation.

Local, State and Federal Funding

As discussed earlier in this section, state and federal funding may be available to volunteer driver programs and sponsoring organizations. In most cases, state and federal funding would be awarded to the Sponsoring Organization. The likely federal funding sources for a sponsoring organization that provides public transportation services in rural and Tribal areas are Section 5310 – Enhanced Mobility for Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities and Section 5311 – Formula Grants for Rural Areas. AmeriCorps - Senior Corps RSVP Grants Competition also provides funding for volunteer driver programs.

The Coordinating Council on Access and Mobility’s (CCAM) Program Inventory identifies 132 federal programs that may provide funding for human services transportation for people with disabilities, older adults, and/or individuals of low income. The CCAM Federal Fund Braiding Guide also includes those federal programs listed in the CCAM Program Inventory.

Local funds or private funds in the form of sponsorships, individual contributions and community donations can have a dramatic impact on a program’s ability to sustain administration and operating needs. The Fundraising by Volunteer Driver Programs Fact Sheet (2021) published as a part of Aging Forward’s (formerly Shepherd’s Center of America) Volunteer Driver Program TurnKey Kit (2021), includes a list of funding methods and sources relevant to volunteer driver programs.

As an example, Ride Connection, which serves the greater Portland region, receives funding from a combination of public and private sources. Public Funding includes TriMet, Metro, state and federal transportation dollars (FTA Section 5310 Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities), and the Statewide Transportation Improvement Fund (STIF). Ride Connection is able to weave these funds with private funding for their administration and operation needs. Read more about Ride Connection in Section 7 - Case Studies.

Coordination and Planning

Volunteer Driver Programs that are funded by Section 5310 – Enhanced Mobility for Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities and Section 5311 – Formula Grants for Rural Areas are required by the Federal law to be included in Coordinated Public Transit Human Services Transportation Plans.

- Requirements for Coordination and Planning are described in FTA Circular (FTA C) 9070.1H: Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program Guidance.

- Programs must be included in locally developed, coordinated plans and approved through a process that included participation by seniors, individuals with disabilities, representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and other members of the public.

- These coordinated plans identify the transportation needs of individuals with disabilities, older adults, and people with low incomes, provide strategies for meeting these needs, and prioritize transportation services for funding and implementation.

Volunteer Driver Programs with Section 5310 funding in urbanized areas must be included in the Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) prepared and approved by the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), the Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) approved jointly by the MPO and the governor, and the State Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP) developed by a State and jointly approved by FTA and FHWA.

Subcontracted Services

A Sponsoring Organization may elect to contract with other organizations that provide volunteer transportation. Most funding agencies require prior approval of all subcontracts. Subcontractors will also need to comply with all of the funding agency's requirements including, but not limited to:

- Non-discrimination

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

- Insurance requirements

- Driver pre-screening requirements

- Driver training

Operating Across Borders

Operating across borders (jurisdictions), including state and county borders, is usually not an issue for volunteer driver programs. When compared to others transit services (i.e., fixed route and ADA complementary paratransit), they are often the most flexible transit service available.

County Borders

The service area of a volunteer driver programs or a sponsoring organizations is often determined locally or dependent on the funding source and contributed local match. Section 7: Case Studies includes many examples of volunteer driver programs that operate across county borders. They include:

New Freedom/Compass IL Transportation Program currently covers 42 counties in Western Wisconsin and requires coordination across numerous agencies and organizations in the region.

Nevada RSVP operates in 15 of the 17 counties in Nevada: Carson City, Churchill, Douglas, Elko, Esmeralda, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, Lincoln, Lyon, Mineral, Nye, Pershing, Storey, Washoe and White Pine. Service Coordinators work closely across counties to coordinate the resources needed to efficiently schedule a ride with one of Nevada RSVP’s volunteer drivers.

Mobility Management

Mobility management is a customer-centered approach to designing and delivering mobility services. The Coordinating Council on Access and Mobility Technical Assistance Center (CCAM-TAC) is a national technical assistance center funded through a cooperative agreement with the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and operated by the Community Transportation Association of America. The CCAM-TAC website includes information and training that may be of value to new and existing volunteer driver programs. According to CCAM-TAC’s What is Mobility Management? web page, Mobility management:

- Encourages innovation and flexibility to reach the "right fit" solution for customers

- Plans for sustainability

- Strives for easy access to information and referral to assist customers in learning about and using services

- Continually incorporates customer feedback as services are evaluated and adjusted

Volunteer driver programs will likely want to seek out opportunities to partner with mobility management services in their area. Most regional planning organizations and some public transportation agencies include mobility management offices. Find out more about mobility management in the Coordination and Mobility Management section of National RTAP’s Transit Manager’s Toolkit. Several of the programs included in Section 7: Case Studies work with mobility managers.

- SAINT participates in the North Front Range Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (NFRMPO) RideNoCo information hub. RideNoCo helps potential riders find the right mobility option for their needs. NFRMPO and RideNoCo work with transportation providers to find transportation options for riders in Northern Colorado. Their work includes the collection of data from riders and transportation providers.

- King County Metro has a contract with Hopelink Mobility Management to provide trip coordination and promotion for its Community Van program.

- The WexExpress Mobility Coordination Office provides transportation services through the WexExpress New Freedom Program for riders who need transportation options beyond those available by other WexExpress services to get to non-emergent appointments across Michigan.

Commercial Motor Vehicles

If the volunteer driver program service is covered by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s (FMCSA) definition of a Commercial Motor Vehicle, the Federal Registration process must be completed with the FMCSA. See the FMCSA’s Do I Need a USDOT Number? website for more information on commercial vehicles transporting passengers. Completion of this process may affect the levels of insurance that the volunteer driver program or sponsoring organization must carry and require other changes in the operation of the volunteer driver program.

Commercial motor vehicle (CMV) means any self-propelled or towed motor vehicle used on a highway in interstate commerce to transport passengers or property when the vehicle:

- Has a gross vehicle weight rating or gross combination weight rating, or gross vehicle weight or gross combination weight, of 4,536 kg (10,001 pounds) or more, whichever is greater; or

- Is designed or used to transport more than 8 passengers (including the driver) for compensation; or

- Is designed or used to transport more than 15 passengers, including the driver, and is not used to transport passengers for compensation; or

- Is used in transporting material found by the Secretary of Transportation to be hazardous under 49 U.S.C. 5103 and transported in a quantity requiring placarding under regulations prescribed by the Secretary under 49 CFR, subtitle B, chapter I, subchapter C.

The FMCSA maintains an online guide, the

Motor Carrier Safety Planner, that is meant to assist CMV operators in understanding and complying with the

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs).

Additional Reading on Other Types of Volunteer Driver Programs

- Independent Living Partnership (ILP) Transportation Reimbursement and Information Program (TRIP) Model. Video: Start a Volunteer Driver Service Today – TripTrakTM software

- ITNAMERICA, a national non-profit network of local transportation providers

- Victor Valley Transit (VVT), Hesperia, California VVT Transportation Reimbursement and Information Program (TRIP) is a self-directed, mileage reimbursement transportation service that complements public transportation. Metro Magazine, November 2018 Victor Valley's volunteer driver program supplements traditional service

- Hamline Midway Elders, St. Paul, Minnesota A part of Minnesota’s Living at Home Network, one of 32 Living at Home Network providers with services that include Volunteer Drivers.

- GWarr Volunteer Driver Programs - Driver Training Toolkit – General Information Fact Sheet 2019, InfoGraph 2019

Section Resources

- 41 U.S.C. Section 8103 - Drug-free workplace requirements for Federal grant recipients

- 42 USC Section 14503 - Limitation on liability for volunteers

- 42 USC Section 14502 – Pre-emption and election of State non applicability

- 49 CFR Part 655 - Prevention of Alcohol Misuse and Prohibited Drug Use in Transit Operations and 49 CFR Part 655.4 - Prevention of Alcohol Misuse and Prohibited Drug Use in Transit Operations, Definitions

- Aging Forward’s (formerly Shepherd’s Center of America) Volunteer Driver Program TurnKey Kit (2021) and Fundraising by Volunteer Driver Programs Fact Sheet (2021)

- Area Agencies on Aging (AAA)

- Arizona - Actions Against Volunteers, Qualified immunity; insurance coverage (Section 12-982).

- Arkansas – Arkansas Volunteer Immunity Act, (ACA Section 16-6-102)

- Chariot, Austin, Texas

- Community Action Agencies

- Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles

- Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA)- FMCSA’s Do I Need a USDOT Number? Website, Definitions and Motor Carrier Safety Planner

- Federal Volunteer Protection Act of 1997 (VPA)

- Florida - Florida Volunteer Protection Act (768.1355).

- Florida Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles

- Florida State Law: Section 320.0848(1)(e) related to parking permits for persons with disabilities

- Federal Transit Administration - 5310 Funding Frequently Asked Questions, Americans with Disabilities: Guidance website, Drug and Alcohol Program website, Section 5310 – Enhanced Mobility for Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities, Section 5311 – Formula Grants for Rural Areas, Section 5311 – Formula Grants for Rural Areas, Coordinated Public Transit Human Services Transportation Plans, and FTA Circular 9070.1H: Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program Guidance.

- Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources (GWaar)- Volunteer Driver Insurance infographic 10-2023, GWarr Volunteer Driver Programs - Driver Training Toolkit, General Information Fact Sheet 2019, and InfoGraph 2019

- Hamline Midway Elders, St. Paul, Minnesota - Living at Home Network, and 32 Living at Home Network providers

- HopeLink’s Community Van Program, Redmond, Washington, King County Metro, Seattle Washington, and King County Mobility Coalition(KCMC)

- Independent Living Partnership (ILP) Transportation Reimbursement and Information Program (TRIP) Model

- King County Mobility Coalition and the Eastside Easy Rider Collaborative’s memo on The Need for Medical Chaperones for Post-Sedation Transportation

- Metro Magazine, November 2018 Victor Valley's volunteer driver program supplements traditional service

- Missouri Department of Transportation’s (MoDOT) List of Recommended Policies for Volunteer Driver Programs

- National Center for Mobility Management (NCMM)

- National Council of Nonprofits webpages: Running a Nonprofit, Cybersecurity for Nonprofits, and State Associations of Nonprofits

- Nonprofit Community Association Handbook, State of Alaska, Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development (2020)

- National Aging and Disability Transportation Center (NADTC), Community Engagement Toolkit: Essentials for Planning & Facilitating Meaningful Conversations

- National Rural Transit Assistance Program (National RTAP) - ADA Toolkit, Substance Abuse Awareness Training, Testing, and Compliance Technical Brief (2022), Transit Manager’s Toolkit/Drug and Alcohol Programs, and Developing and Maintaining a Transit System Personnel Policy Brief

- Nonprofit Risk Management Center (NRMC) Articles: Take Action on Risk: Make a Plan, Not a List - NRMC-Risk-Management-Essentials-Fall-2022-Newsletter, Transporting People: What to Consider - NRMC-Risk-Management-Essentials-Summer-2023-Newsletter, Volunteer Protection Act – Ten Years Later, October 2009, State Liability Laws for Charitable Organizations and Volunteers, What Basic Insurance Coverage Should a Nonprofit Consider?, and Risk on the Road: Managing Volunteer Driver Exposures

- North Front Range Metropolitan Planning Organization’s (NFRMPO) RideNoCo

- Ride Connection, Portland, Oregon

- Risk Management and Insurance, Arizona State University (ASU) Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation

- Rural Health Information Hub (RHIhub), Volunteer Models for Rural Transportation website.

- SAINT Volunteer Transportation, Fort Collins, Colorado

- Texas Department of Transportation, Texas Rural Microtransit Guidebook, Develop a Branding, Marketing and Outreach Plan

- Tips for Understanding Volunteer Insurance, Volunteers and Insurance Fact Sheet (2023) Wisconsin Office of the Commissioner of Insurance

- Victor Valley Transit (VVT), Hesperia, California - VVT Transportation Reimbursement and Information Program (TRIP), and Metro Magazine, November 2018 Victor Valley's volunteer driver program supplements traditional service

- Volunteers in Motion, Florida

- Volunteer Driver Insurance in the Age of Ridehailing, AARP (September 15, 2020) By Jana Lynott, Public Policy Institute, Johanna Zmud, Gretchen Stoeltje, Todd Hansen, Tina Geiselbrecht, Chris Simek, Ben Ettelman, Texas A&M Transportation Institute & Wendy Fox-Grage

- Washington Nonprofit Handbook, How to Form and Maintain a Nonprofit Corporation Washington State – 2022 Edition

- Washington State Department of Licensing

- Washington State Law: RCW 24.06.035 Indemnification, RCW 46.19.020 for Eligible Organizations

- Washington – Liability of volunteers of nonprofit or governmental entities (RCW 4.24.670).

- Washington – Private, Nonprofit Transportation Providers, Insurance (WAC 480-31-070)

- WexExpress New Freedom Volunteer Driver Program - Rider Resources, Mobility Coordination Services, Become A Volunteer, Local News Coverage Video: The New Freedom Volunteer Driver Program Introduced On the four.

- Wisconsin State Legislature – Limited Liability of Volunteers (181.0670)

Updated October 2025

National RTAP offers one-stop shopping for rural and tribal transit technical assistance products and services. Call, email, or chat with us and if we can’t help with your request, we’ll connect you with someone who can!

" National RTAP offers one-stop shopping for rural and tribal transit technical assistance products and services. Call, email, or chat with us and if we can’t help with your request, we’ll connect you with someone who can! "

Robin Phillips, Executive Director

" You go above and beyond and I wanted to let you know that I appreciate it so much and always enjoy my time with you. The presentations give me so much to bring back to my agency and my subrecipients. "

Amy Rast, Public Transit Coordinator Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans)

" I always used the CASE (Copy And Steal Everything) method to develop training materials until I discovered RTAP. They give it to you for free. Use it! "

John Filippone, former National RTAP Review Board Chair

" National RTAP provides an essential service to rural and small transit agencies. The products are provided at no cost and help agencies maximize their resources and ensure that their employees are trained in all aspects of passenger service. "

Dan Harrigan, Former National RTAP Review Board Chair

" We were able to deploy online trip planning for Glasgow Transit in less than

90 days using GTFS Builder. Trip planning information displays in a riders'

native language, which supports gencies in travel training and meeting Title VI

mandates. "

Tyler Graham, Regional Transportation Planner Barren River Area Development District

Slide title