Electric Vehicle Maintenance Best Practices

By National RTAP, Shared-Use Mobility Center (SUMC), and Transit Workforce Center (TWC)

November 2022

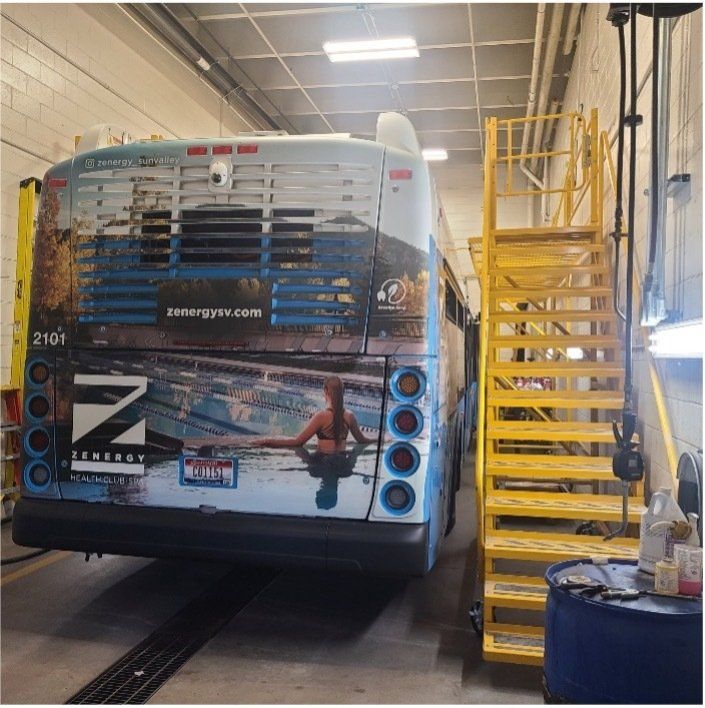

(Photo credit: Fresno County Rural Transit Agency - FCRTA)

Introduction

Zero-emission bus (ZEB), electric bus, and battery-electric bus (BEB) adoption has been increasing over the past decade and is expected to continue to rise. According to the most recent U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics data, there were 761,100 sales of hybrid and electric vehicles in 2020. While most people concur that zero-emission vehicles are better for the environment, public health, and global sustainability, less is known about maintenance requirements for these vehicles. This best practice spotlight article on electric vehicle maintenance, prepared collaboratively by National RTAP, Shared-Use Mobility Center (SUMC), and Transit Workforce Center (TWC), provides recommended practices and case studies from transit agencies that have successfully implemented these vehicles into their fleets.

Challenges and Solutions

While electricity and battery-powered vehicles are not new (electric trackless trolleys debuted in 1882 and cars began including batteries in the 1910s), today’s ZEBs rely on a battery charging infrastructure to keep them operational. ZEBs consist of two propulsion types. BEBs require either wayside or in-depot charging equipment, while fuel cell buses (FCBs) typically require infrastructure to store and dispense liquid hydrogen. Both present a unique set of challenges. This section provides recommended solutions, related primarily to BEBs.

Education and Training

A survey in TCRP’s

Battery Electric Buses—State of the Practice conducted by the Center for Transportation and Environment found that most transit agencies conducted electric vehicle maintenance activities in-house, followed by having the original manufacturer perform maintenance, and fewer agencies outsourcing this function to a third-party.

The 2021

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Section 30018 states that 5% of grants related to zero-emission vehicles must be used by recipients to fund workforce development training, including registered apprenticeships and other labor-management training programs. This applies to both the Low or No-Emission (Low-No) Bus Program and Grants for Buses and Bus Facilities. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Fiscal Year 2021 Low-No Bus Program awardees included workforce development and training on electric fleet maintenance and management for Pioneer Valley Transit Authority, the regional transit authority for 24 municipalities in Western Massachusetts, and for Tri-Valley Transit in Vermont to train its mechanics and drivers.

The

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 also provides funding for workforce development and training to support the maintenance, charging, fueling, and operation of zero-emission vehicles

Transit agency staff need training on pre- and post-inspection, emergency procedures, and preventive maintenance on electric bus features that are not found on conventional buses. Drivers need to be trained on how to read and understand diagnostic systems and know when to contact dispatch for further assistance.

They should also be trained on on-road charging procedures as applicable. Maintenance staff and emergency response personnel need to fully understand basic electrical systems before making the transition to high-voltage applications. They should also have the ability to read electrical schematics and diagnose and repair systems specific to zero-emission vehicles, such as energy storage systems, procedures to safely de-energize buses from high voltage, electrically-powered auxiliary systems, and electric propulsion systems.

FTA funds the Transit Workforce Center (TWC), administered by the International Transportation Learning Center in Silver Spring, Maryland, to provide technical assistance to transit agencies planning and implementing new workforce development initiatives including zero-emission vehicle training.

Additional FTA grantees include the West Coast Center of Excellence in Zero Emission Technology (CoEZET), hosted by SunLine Transit Agency. CoEZET is a collaboration between public and private organizations, including transit agencies, colleges, private industry, and government agencies, that focuses on training for the maintenance of zero-emission buses. The Center has also been funded for a dedicated zero-emission maintenance facility which will be used to demonstrate many of the diagnostic tools necessary to maintain zero-emission fleets.

Training courses include the SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) International’s Hybrid and Electric Vehicle Engineering Academy and ZEB University at AC Transit. As more ZEBs are adopted, it is likely that more training courses will become available from various organizations.

Case Studies

Case Study: Fresno County Rural Transit Agency

Case Study: Mountain Rides Transportation Authority

Cold weather has been the biggest challenge for this Idaho transit agency. There was one day which the average temperature was negative 5 degrees Fahrenheit, and the driver was able to bring the bus back to the garage in the nick of time by watching the battery charge closely. Training for drivers included how to pay attention to safe levels of charging in various situations. Since Mountain Rides drivers care a great deal about their buses, they have been “owning, loving, and wanting peak performance for their new electric vehicles,” said Wally Morgus, Executive Director. Mountain Rides decided not to purchase a booster heater for their batteries as they want to be completely electric.

Ben Varner, Director of Assets and Planning, believes that preventive maintenance is key to maintaining a safe and efficient fleet. The maintenance team follows the manufacturer's recommendations for quarterly maintenance checks and service at various intervals, such as every 6,000 miles. The maintenance team also uses the manufacturer’s reporting system to help with preventive maintenance and to stay ahead of the curve, by taking a deep dive into potential situations of battery depletion. Early on in their electric vehicle transition, a driver was concerned that the battery was too low and brought the bus into the depot. The report showed that the battery was right where it should be with the reserve, which turned into a teachable moment for that driver and for all the drivers. Varner also stresses the importance of having a close relationship with the area’s electric utility and says that “partnership is key.”

Mountain Rides is known for thinking outside the box and its electric vehicle maintenance strategy provided the first of many opportunities to do so for its new fleet. For the batteries that are mounted on top of the roofs of the buses, they were able to purchase a special scaffolding, so maintenance staff had easy and safe access to the equipment.

Case Study: SporTran

Many rural areas are turning to electrical co-ops to coordinate their electric vehicle initiatives. The co-ops can serve many rural communities simultaneously. Organizations like the

National Rural Electric Cooperative Association and the

Electric Vehicle Consortium can provide information on electric co-ops.

FCRTA (see case study above) wants to share their lessons learned and best practices with all who can benefit from them and publish their documents like their

Grid Analysis Study publicly. General Manager Moses Stites and Operations Manager Janelle Del Campo welcome questions from other agencies regarding electric vehicles. The agency also coordinates with the 13 Public Works yards in rural Fresno County to install chargers and worked with local law enforcement and first responders to coordinate training for catastrophic events (including terrorism) using the FRCTA electric vehicles.

In Shasta Regional Transportation Agency's

work program for the county, part of their plan was to consider opportunities for partnership and/or training programs with local or regional colleges for alternative fuel, hybrid or electric vehicle maintenance.

- Agencies must submit a Zero Emission Fleet Transition Plan as a requirement for participation in the Low-No Emissions Grant program. The plan should include details on how the transition will impact the existing frontline workforce, including plans for training incumbent maintenance workers.

- It is a good idea for requests for proposals and contracts to specify that the manufacturer will train agency personnel.

Providing Training for Zero Emission Buses: Recommended Expanded RFP Language provides detailed information on this topic.

- The manufacturer is responsible for ensuring that frontline agency workers are trained to safely perform maintenance.

- When hiring, prioritize individuals with previous electrical skills, licenses, and/or certifications.

- Train bus operators to charge their own buses via both depot and in-route charging methods.

- Vehicles do not need dedicated chargers. A schedule can be made for multiple vehicles to use the same charger. Charge, when possible, at times when electricity costs are lower.

- Explore the possibility of negotiating a locked-in reduced rate with the utility.

- It is a good practice to buy buses and charging infrastructure from the same manufacturer, if feasible.

- Check the battery warranty. Work with manufacturers and with agency maintenance personnel to determine the best warranty language for your agency.

- Maintain an inventory of spare parts needed for emergency situations.

- Consider letting BEV drivers who use their own vehicles to charge their vehicle at their homes overnight to take advantage of lower nighttime electricity rates if it is feasible to install charging infrastructure and reimburse employees.

- Test the battery capacity at regular intervals.

- If agencies can automate their bus yard and install corresponding software in their buses (some vehicles come with this), buses can be pre-scheduled to automatically travel to overhead charging stations at regular intervals.

- Plan for the potential need to purchase new chargers or other equipment as the grid infrastructure changes. Explore modular charging infrastructure, which may enable agencies to expand the charging capacity with the proper equipment. Plan for the need to replace or upgrade charging infrastructure early.

- If buses are not in use for long periods of time, batteries can still lose charge and it is important to check the level of charge (keep them at a charge of 25-75% if they are going to remain unused).

- Try to store battery-electric buses and batteries in a shaded, climate-controlled environment, generally between 40-86 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Train drivers on energy-efficient driving behaviors. Drivers should understand the difference between driving an EV and an Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicle. They should be introduced to the concept of regenerative braking and how to maximize regeneration by planning out their stops. There should also be an introduction to the differences in energy consumption when accelerating or maintaining speed in EV’s vs. ICE’s.

The following tips from Andrew Walker, Ford Pro EV product marketing manager were published in How to Improve EV Battery Performance in Cold Weather: (see the further information section)

- Drive at moderate speeds when possible.

- Use “Eco” or “L” drive modes to help recover more energy from the battery when road permissions permit.

- Avoid harsh acceleration and braking to help maximize battery range.

- Keep doors and windows closed when running the heat or air conditioning to conserve energy.

- If the vehicle is covered with snow, start it remotely or schedule preconditioning to melt snow, and brush off any remaining snow before driving to eliminate extra weight and drag.

Acknowledgements

National RTAP is grateful to the following individuals for their contributions and reviews: Douglas Nevins, Researcher, James Hall, Program Manager, Technical Training, John Schiavone, Program Director, Xinge Wang, Deputy Director, Jack Clark, Executive Director, Transit Workforce Center; Moses Stites, General Manager, and Janelle Del Campo, Operations Manager, Fresno County Rural Transit Agency (FCRTA); Wally Morgus, Executive Director, Carlos Tellez, Maintenance Manager, and Ben Varner, Director of Assets & Planning, Mountain Rides Transportation Authority; Shauna Miller, RTAP Program Manager, Idaho Transportation Department.

Further Information

Aamodt, Alana, Cory, Karlynn and Kamyria Coney.

Electrifying Transit: A Guidebook for Implementing Battery Electric Buses. National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL), 2021.

Collision Repair,

Refurbishing and Remanufacturing: Electrical Component Damage. BusRide Maintenance, October 1, 2018.

Huggett, Amanda.

How Fleet Technician Roles Will Change in an Electrified Environment. Automotive Fleet, May 3, 2022.

International Transportation Learning Center and Jobs to Move America.

Providing Training for Zero Emission Buses: Recommended Expanded RFP Language. 2022.

Mallia, Eric.

What Should I Know about Employees Charging at Home? Fleet Forward, May 31, 2022.

Metro Magazine.

What Maintenance Teams Need to Know Before Adding Electric to the Mix. 2022.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Battery Electric Buses—State of the Practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Guidebook for Deploying Zero-Emission Transit Buses. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2021.

Prejean, Louis.

How to Improve EV Battery Performance in Cold Weather. Government Fleet, July 14, 2022.

Skolrud, Severin.

Achieving Low-Carbon Benefits from Bus Yard Automation. Mass Transit, May 31, 2022.

ViriCiti.

New Electric Vehicle Maintenance Skills for Maintenance Technicians. Florida Public Transit Association Newsletter, Fall 2020.